Back المطالبة العثمانية بالخلافة الرومانية Arabic Prétention ottomane à la succession romaine French Rivendicazione ottomana alla successione di Roma Italian د عثماني سترواکۍ ادعا د روم د ځایناستي په توګه Pashto/Pushto

After the conquest of Constantinople in 1453, the sultans of the Ottoman Empire laid claim to be the legitimate Roman emperors, in succession to the Byzantine emperors who had previously ruled from Constantinople. Based on the concept of right of conquest, the sultans at times assumed the styles kayser-i Rûm ("Caesar of Rome", one of the titles applied to the Byzantine emperors in earlier Ottoman writings) and basileus (the ruling title of the Byzantine emperors). The assumption of the heritage of the Roman Empire also led the Ottoman sultans to claim to be universal monarchs, the rightful rulers of the entire world.

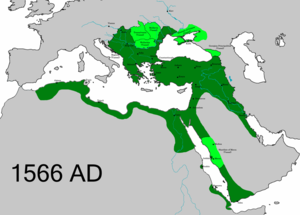

The early sultans after the conquest of Constantinople–Mehmed II, Bayezid II, Selim I and Suleiman I–staunchly maintained that they were Roman emperors and went to great lengths to legitimize themselves as such. Greek aristocrats, i.e. former Byzantine nobility, were often promoted to senior administrative positions and Constantinople was maintained as the capital, rebuilt and considerably expanded under Ottoman rule. The administration, architecture and court ceremonies of the early post-1453 Ottoman Empire were heavily influenced by the former Byzantine Empire. The Ottoman sultan also used their claim to be Roman emperors to justify campaigns of conquest against Western Europe. Both Mehmed II and Suleiman I dreamt of conquering Italy, which they believed was rightfully theirs due to once having been the Roman heartland.

Although the claim to Roman imperial succession never formally stopped and titles such as kayser-i Rûm and basileus were never formally abandoned, the claim gradually faded away and ceased to be stressed by the sultans. The primary reason for the break with claiming Greco-Roman legitimacy was the increased transformation of the Ottoman Empire to claiming Islamic political legitimacy from the 16th century onwards. This was the result of Ottoman conquests in the Levant, Arabia and North Africa having turned the empire from a multi-religious state to a state with a clear Muslim majority population, which necessitated a claim to legitimate political power rooted in Islamic rather than Roman tradition. The shift in Ottoman identity also resulted from conflict with the Safavid Empire in Iran, which followed Shia Islam, leading to the sultans more strongly embracing and stressing their Sunni Islam faith. Kayser-i Rûm was last used officially in the 18th century and Greek-language documents ceased to refer to the sultan as basileus at the latest in 1876, whereafter the Ottoman rulers were titled in Greek as soultanos and padisach.

Recognition of the Ottoman claim to be Roman emperors was variable, both outside and within the Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans were widely accepted as Romans in the Islamic world, with the sultans being recognized as Roman emperors. The majority of the Christian populace of the Ottoman Empire also recognized the sultans as their new emperors, but views differed among the cultural elite. Some saw the Ottomans as infidels, barbarians and illegitimate tyrants, others saw them as divinely ordained as punishment for the sins of the Byzantine people and others yet accepted them as the new emperors. From at least 1474 onwards, the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople recognized the sultans by the title basileus. Whereas views were variable in regards to the legitimacy of the Ottomans as sovereigns, they were consistent in that the Ottoman Empire as a state was not seen as the seamless continuation of the Roman Empire, but rather its heir and successor, as the former empire had far too deep theological roots to be compatible with a foreign Muslim ruler. Thus, the former Byzantines saw the Ottoman Empire as inheriting the political legitimacy and right to universal rule of the preceding empire, but not its other theological implications. In Western Europe, where the Byzantine emperors had not been recognized as Roman either, the Ottomans were generally seen as emperors, but not Roman emperors. Views on whether the Ottoman sultans were the successors of the Byzantine emperors or a completely new set of rulers varied among westerners. The right of the Ottoman sultans to style themselves as Roman emperors and claim universal rule was challenged for centuries by the rulers of the Holy Roman Empire and the Russian Empire, both of whom claimed this dignity for themselves. The different emperors sometimes recognized the others as being of equal rank or higher rank, such as the Holy Roman recognition of the Ottoman sultan as superior in the 1533 Treaty of Constantinople and a more equal mutual recognition between the two in the 1606 Peace of Zsitvatorok.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search